Category — Coming of Age

A WALKER IN THE CITY

Roll it . . . I buy a slice of pizza on Broadway and walk by the Cooper Union, then down St. Mark’s Place. I notice the Fillmore East is going to reopen as a circus. I go up Second Avenue and see bus ads that say Prisoner of Second Avenue on them. That’s a Neil Simon play. (When Simon was on Dick Cavett, Simon said his problem was he couldn’t stop writing.)

I arrive at 215 Second Avenue, my destination. I’m thinking of renting a room here, but the sublet guy isn’t home. A friend of his is in. He’s Joel. Another guy is here, too. He’s Joe. The guy I’m looking for is Joey. The place is a dump. All these guys are crashing here. Joel has a hacking cough and a pornographer’s beard. The windows are dirty and have iron gratings. I’ll take the place.

I use Spic and Span to clean the refrigerator and kitchen table. Joel says, “Don’t be so middle-class about it.” Joel is a graduate of Queens College, as are Joe and Joey. Joel spits blood in the toilet and doesn’t flush it. He floats his pink toilet paper! The cat shit is encrusted all over the bathroom. Joe is the editor of Monster Times.

I head over to Greenwich Village. I know a recent Brandeis graduate there who has enrolled in NYU law school. He lives on Waverly Place and is seemingly normal. He’s not in. I go to Fifth Avenue and look up a girl whose father I know from Cleveland. The doorman says I can buzz her. “I’m Bert,” I say on the intercom.

“Who?”

“Bert like in Bert Parks.”

This girl is a buyer for Bloomingdale’s. She’s heading out to New Jersey for a grand opening. I head over to the 34th Street YMCA, where I’ll spend the night, I think. A girl there — at the Y — asks me, “Where are you from?”

“Michigan.” (Michigan is cooler than Ohio.)

“I’m from Minnesota!” she says. She says she’s going to be an actress. Her boyfriend shows up.

Walkin’.

April 13, 2022 3 Comments

WITH THE RED CAVALRY, CLEVELAND

Most every Jewish baby boomer in Cleveland grew up around Holocaust survivors, unless he lived in Shaker Heights, and even in Shaker there were probably a few DPs in the double houses.

I had a classmate at Brush High who retold his parents’ Nazi horrors to the local newspaper in the 1960s — pre-Holocaust (before the word Holocaust went big-time). Joe was a super Jew. Joe’s father worked at a kosher poultry market. Joe often stayed home for obscure (to me) Jewish holidays. Some of the Jewish kids teased him when he came back. (The goys didn’t notice.)

I copied Joe’s style. I wrote a letter to the Cleveland Press protesting the U.S. Christmas stamp, which had a religious symbol (Madonna and child), 1966. I said the new stamp violated the separation of church and state. I got letters back. One reader wrote, “Go to Vietnam where men are men and not homosexual like you.” That got me to write more letters. I wrote about Poland expelling its last Jews in 1968. I vied with Joe for champion of Jewish teenage letter writers. All I had to do was write Jew, and I would get half-baked, vitriolic feedback. I enjoyed that. I had been through so little. I wanted to experience World War II. Then I’d go home and eat some Jell-O.

—

Alex Kozak sold record albums and sewing machines. Appliance store owners used to sell records; I got Bechet of New Orleans and Be Bop Era (RCA Vintage Series) from Mr. Kozak. He was a World War II  Red Army veteran — a Hungarian Jew who escaped the Nazis and fought with the Russians. I borrowed his cavalry boots for my high school Canterbury Tales presentation. Mr. Kozak was big — about one-and-a-half Isaac Babels.

Red Army veteran — a Hungarian Jew who escaped the Nazis and fought with the Russians. I borrowed his cavalry boots for my high school Canterbury Tales presentation. Mr. Kozak was big — about one-and-a-half Isaac Babels.

I knew Mr. Kozak through my parents, who often socialized with Holocaust survivors. My dad liked the men; many were into baseball and were for the most part no-nonsense. What was there to talk about — the good old days? Keep it short. My dad liked that.

At a Yiddishe Cup gig in Detroit, I ran into Mr. Kozak’s daughter. She said her nephew had the cavalry boots now — the ones Mr. Kozak had worn into Prague with the Soviets in 1945.

Lime Jell-O. That was the best.

—

“Joe” is a pseudonym, re: my high school friend.

February 16, 2022 5 Comments

MAKING THE SCENE (PART II)

This is a guest post by Mark Schilling. It’s an edited excerpt from an unpublished novel Mark wrote in 1973. (The character “Bruce” is based on yo.)

Bruce answered my questions about his trip to Puerto Rico in a monotone, with that dry humor of his, never looking at me and seldom saying more than the minimum. Wanting to cheer him up, I suggested we go to The Scene — the bar famed for having the only psychedelically lighted dance floor in Ann Arbor. I said, “Maybe we can pick up some secretaries from Ypsilanti and tell them we’re pre-med students.”

Bruce agreed to go. “But no junior high school shit,” he said. “No standing around for an hour to get the feel of things. We walk up to the first two hip-looking girls we see and ask to sit down with them.”

“You take the lead, man.”

“Don’t try to bring me down, I’ll need all the help I can get,” Bruce said.

“I’m not going to bring you down,” I said, feeling pissed. But I let it ride.

The Scene was packed. It was Saturday night. The drummer and keyboard player, who accompanied the records, were taking a break. Bruce and I stood at the bar surveying the crowd. “See the two chicks in back?” Bruce asked. “I’ll go over and see if it’s cool. Just stay here.” One, with her back to us, was wearing a red bandana. The other, a blonde, looked fantastic.

What was Bruce going to say? Hi, my friend and I would like to sit with you? I hoped it would be something better than that, but what? Bruce waved me over.

Now it was my turn to feel the butterflies. Bruce was sitting next to the blonde. The girl with the red bandana had a friendly, intelligent smile, which made me wonder what she was doing at The Scene. We covered everyone’s name, occupation and place of residence. The bandana girl, Jane, was a natural resources student at the U of M; the blonde, Marie, was a drop-out from Wayne State, now working as a check-out clerk at a Kroger’s in Detroit.

Bruce asked Marie who her favorite authors were, as a ploy for recounting his own poetic and journalistic exploits (he wrote music reviews for the college newspaper). When she told him she had read On the Road, he looked as though he was going to hug her. “You know Kerouac! What else have you read?” All interesting, but with the music blasting away it was hard to hear half of what they were saying.

So I quizzed Jane about her major. She was very concerned about the environment. “We’re running out of time,” she told me. “We’ve got to make changes now. In twenty years it will be too late.” She didn’t know what to do about it and neither did I. We danced, talked some more, and then Jane and Marie had to leave. Bruce wrote Marie’s number down on a napkin.

Walking back to campus, Bruce said, “Her name is Marie Verdoux. She’s a Frog — a Canuck!” Bruce had wanted to meet a French girl ever since becoming a fan of Kerouac, that son of Canucks. “She’s a genius, no doubt about it.”

A couple days later I dropped by Bruce’s place, a rooming house just off State Street. He was sitting on his bed listening to records. He’d been at it for hours. Bruce told me he had called Marie. “She was surprised but I think she dug it,” he said.

“What did you talk about?”

“Bullshit. I was just doing it to keep my edge. I don’t want her to forget who I am, you know.” Then Bruce rambled on more about Marie — what a good time they would have together. Bruce liked to make every encounter with a girl into a big moment of truth, a matter of make or break. We could endlessly analyze the nuances of these meetings. Bruce said, “I tape-recorded the call. She has an incredible voice, like an airline stewardess or something.”

Bruce tape-recorded nearly everyone who walked into his room or talked to him on the phone. It bugged me at first to see him flipping that thing on at the start of a conversation, but I’d gotten used to it. Bruce said he was making the tapes for posterity. He liked to quote Ed Sanders’ adage “this is the age of investigation and every citizen must investigate.”

This tape — this blog post, label it “The Scene, 1973.”

Mark Schilling, 1977

— Mark Schilling has lived in Japan for decades and writes regularly for The Japan Times and Variety. His books include Sumo, A Fan’s Guide; Tokyo After Dark; The Encyclopedia of Japanese Pop Culture; and most recently Art, Cult and Commerce: Japanese Cinema Since 2000.

January 12, 2022 9 Comments

MY BEAT-EST FRIEND

Mark Schilling was my beat-est buddy. He moved to Los Angeles, quite possibly to live out a Charles Bukowski fantasy. Before L.A., Mark was in Ann Arbor, where he did some cool things (can’t remember any of them) and some cloddish things, like going out on a first date and taking one dollar with him, and the girl said, “Do you think I’m paying for myself.”

“Yes,” Mark said.

Mark showed up at my place. “Just blew another one!” he said. We played the Best of the Beach Boys, Vol 2, and Mark sang along. He had a good voice. We hopped into Mark’s Chevy and made the scene — The Scene bar in downtown Ann Arbor. The bar had flashing colored lights, nude photos of women on the ceiling, and peace and love posters. The Scene was cheesy, an ersatz European discotheque. Stupid. The more philosophical heads in town were at Flick’s Bar or Mr. Flood’s Party. But Mark and I preferred the drama of The Scene, because at The Scene there was dancing, which could lead to . . . whatever. The Scene had a contingent from Ypsilanti that could go nuts at any moment.

I approached a girl called Pinball Annie, who was next to the speakers. She refused to budge, and I didn’t feel like going deaf, so Mark and I retreated to the loft, above the dance floor. The viewing was good up there, and Mark and I were above-average voyeurs. (Below-average players.) Mark talked about his student teaching and what he’d been reading lately. Mark worshipped Henry Miller. Mark was all about Hen (Miller) and Buk (Bukowski). Mark also admired Anais Nin, who lectured once at U-M. She defended Henry Miler before a crowd of Miller-hating women. She said Miller’s writing was picaresque.

Mark was picaresque, too. (Picaresque: “relating to an episodic style of fiction dealing with the adventures of a rough and dishonest but appealing hero.”) Mark was all that, but honest.

Mark sold Christmas trees in L.A., then moved to Tokyo to teach English at Sony. He quit the Sony ESL gig after a few years and wrote books and articles about Japanese culture. One of Mark’s first books was a guide to nightlife, Tokyo After Dark. Figures.

Bert Stratton (L) and Mark Schilling. 1971. A2.

P.S. Mark is still my beat-est buddy.

—

I recently wrote a book review of Donald Hall’s Old Poets for City Journal. The review is titled “A Viking Cruise for Old English Majors.”

January 5, 2022 7 Comments

ROBERT BLY’S WORST NIGHTMARE

Poet Robert Bly’s worst nightmare was visiting his family in Minnesota and attending hockey games. Maybe not as bad as Vietnam, but up there pain-wise, he said.

Bly’s anti-Midwest rap was a big hit in Ann Arbor in the 1970s. Bly’s main message: your parents are middle-class stiffs; your real family is elsewhere. Join the counterculture. Bly was a 44-year-old Harvard man in a serape. He had a lot of chutzpah dispensing life advice wearing that shmate.

Bly died at 94 in Minnesota last month. He lived in Minnesota most of his life and was the state’s first poet laureate, so he was putting us on when he said don’t go home.

I liked going home. Whenever I came home from college, I received the treatment due the future Dr. Stratton. I only had to do the occasional minor chore, like emptying the dishwasher or dusting. Some of my college buddies didn’t go home. They were scared of becoming middle-class, even for a single weekend.

During college vacations I sometimes hung around with my grade-school neighborhood pals. My friend John was installing tanning booths. My friend Chuck owned shares in a racehorse. Chuck worked as a mutuel clerk at the day-time Thoroughbred track and at the trotters’ track at night. When Chuck wasn’t working, he was firing his .357 magnum at beer cans in the woods in Geauga County.

I learned something about guns. Not a lot, but enough to swiss-cheese any intruder with a 12-gauge shotgun. Bly knew about guns, too, and Midwestern culture. But it wasn’t his thing. Or maybe it was.

December 22, 2021 1 Comment

ALL BUT EAGLE

Be prepared . . .

The lead singer in Yiddishe Cup, Irwin Weinberger, is A.B.E. (All But Eagle). He tried to get an Eagle Scout badge as an adult, but the national office wouldn’t give him the badge. I’ve seen Irwin swim. He can do it now, HQ!

Irwin Weinberger, 11, and his father, Herman (with cig), 1966.

If the Scouts would give Irwin the badge, he would donate money to the Scouts. (My guess.)

Did Irwin ever get the Ner Tamid religious service medal? (Yes.)

The Boy Scouts religious service medals — like the Ner Tamid thing — were attractive because they were real medals. For the Episcopalians and other Christians, the medals looked like British flags, with lots of crosses. Very cool. The Ner Tamid medal was an eternal light. Not as cool, but cool.

Boys’ Life. I miss that mag. Then again I miss a lot of things, and Boys’ Life is way down the list.

Just above Bosco.

I’ll miss Irwin. He’s moving to North Carolina. Fly like an eagle, brother.

—

Steven Greenman (violin, vocals) and Mark Freiman (trumpet, vocals) are joining Yiddishe Cup in January.

Irwin’s first Yiddishe Cup gig was a bar mitzvah luncheon at Suburban Temple, Beachwood, in 1990. His final Yiddishe Cup gig was last week at Wiggins Place, an assisted-living facility in Beachwood. Join Yiddishe Cup and see Beachwood!

December 8, 2021 6 Comments

HOMEBOY

I spent my entire childhood in the same house. Nothing moved. I certainly didn’t. I knew where everything was. In 1951 I think my dad told a builder something like “build me a house.” That simple. A three-bedroom colonial in South Euclid.

I bounced a basketball in the driveway at all hours. That really annoyed the old man next door who was ill. I blared clarinet. That was also annoying. Everything was new and grand. The car wasn’t new, but it was grand. A used Ford.

My mother had a second phone line installed in the kitchen for my parents’ door-to-door cosmetics company, Ovation of California. The phone was a Princess. It was sleek and rarely rang. That business went under. In the basement, my dad had a lab where he made foot powder. I could go on (like I did in a recent Wall Street Journal article about my dad). Here’s a new one on Toby: my dad wanted to collaborate with Case profs/scientists to make a toaster that would take the calories out of bread. No takers from Case.

My friends and neighbors never moved. John, across the street, died of alcoholism and mental illness in 1992. He lived in the same house his whole life — 41 years.

I think of going back there, to my old house. I drive near there. I decide against it. Best to go by bike and get the full flavor.

My dad worked for a key company, which almost transferred him. Here are the three “almost transferred” cities: Edison, New Jersey; Richmond, California; and Toronto.

I often meet people who moved so frequently as children they don’t have a hometown. That’s not me.

November 10, 2021 7 Comments

REPORTING FOR DUTY

I traveled a lot in my twenties. I hitchhiked across America four times. I also went from Tijuana to Colombia by bus. I went everywhere. I wrote novels too, which went nowhere.

You can’t take a bus all the way to Colombia. The road doesn’t go through the Panama jungle. I flew from Costa Rica to San Andres island to Barranquilla, Colombia.

I came home eventualmente and at age 25 started working part-time for my dad, painting apartments and pointing bricks. That was the end of the road pretty much, but I continued writing. I wrote mostly about Cleveland. I was trying to be Don Robertson / Herbert Gold. By the way, Gold is still alive (97). I got a job as a beat reporter and wrote about cops and robbers, and even wrote a police-procedural novel about a Slovenian-American cop in Collinwood. The writing was a diversion. Working for the old man was no picnic.

I got married and had kids. That was a good move. Raising kids . . . I was so busy I didn’t have time to think or get down on myself. I reported for duty.

These days I don’t report for duty as much as I used to. I hope Menorah Park reopens to “essential volunteers” soon, so I can toot my clarinet in the hallways there. But now, with the delta variant, that reopening is getting pushed back again. If I disappear tomorrow, my clarinet-playing might be the one thing the locals miss. My property management game counts too — don’t knock the bricks-and-mortar game. And don’t forget the writing game.

Stop saying “game.”

August 25, 2021 No Comments

IS IT ROLLING, BOB?

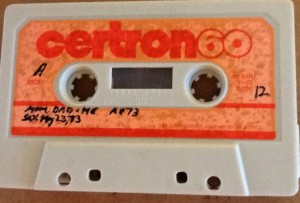

When I audiotaped my parents at dinner in 1973, I told my dad I was doing cinema verite. Don’t knock it. Louis Armstrong did a lot of audiotaping. Decades later, I played my 1973 audiotape for my adult children. My son Ted said, “You’re weird, recording everything.”

In the tape, my parents asked me questions about my college roommates.

For instance, my mother said, “What is Billy from the dorm doing?” I stonewalled my mom. Nevertheless, the tape is somewhat interesting, even the silences. As Ed Sanders once said: “This is the age of investigation and every citizen must investigate.”

“I don’t want any dessert” — that kind of thing. That’s what’s on the tape. I hope my kids throw it out. Or I will. I definitely will. There’s a bad sax solo by me on the flip side.

My dad: “What the hell you got the tape recorder on for? There’s nothing going on.”

July 21, 2021 4 Comments

THE SOCIALLY AWKWARD

BOYS CLUB

The Intakes, a boys club, was a throwback to a Depression-era, settlement-house group. The Intakes met at the Mayfield Road JCC, a successor institution to the Depression-era Council Education Alliance. The Intakes’ purpose was to keep teenage boys off the streets, which wasn’t too hard because, in our case, we studied so hard we rarely went out.

The Intakes president had a regular excuse for not partying on Saturday night: “I’ve got too much homework.” One summer he got a grant to study the crystal structure of molecules at a university. He did his undergrad at MIT, then went on to med school.

The Intakes didn’t “intake” girls. We played poker, miniature golf, bowled and held meetings. Our advisor was a social worker from New York. He often called us schmucks, which we found endearing. We talked about where to spend our money, earned by selling salamis and Passover macaroons. Should we go to New York or Washington?

We rode the Hound to New York and visited the Statue of Liberty, saw Jeopardy live, and ate at Katz’s Deli. I bought Existentialism Versus Marxism in a Greenwich Village bookstore. I haven’t finished it yet.

The Intakes folded after twelfth grade. There are some other ancient-history Jewish boys clubs around town. I heard of one the other day, the Regals. They were from Kinsman. They were a generation older than my guys. The Regals are truly out of business.

Intakes, 1967. Poker game.

April 28, 2021 5 Comments

MAX

Max Burstyn lived in the Jewish highlands on the other side of the public park from me. No flooding in the highlands, and 99-percent yidlach. Max spoke English, Yiddish and German. Max was born in Munich and came to America as a baby in the 1950s. His dad was a Galitzianer from Krakow.

Max Burstyn, 1969

I played tennis with Max in the park. That’s where we met. Max still rants about my neighborhood — the lowlands, the other side of park. He says, “You lived with the goys — like Stropki. I played Pony League with him. There were about eight Stropkis. What about Bobrowski? He was a Catholic too. Went to St. Joe’s. He played third-string for the Browns. He was from your street. There was Mastrobuono. He had a funny walk.”

Max was a mischling ersten grades, self-described. (First-degree mixed race.) That’s a Nazi term, but Max used it — at least around me. Max’s mother was a German gentile. Max’s father and mother met in Germany after the war. Max was halachically converted as a baby.

Max knows some strange Yiddish words. He mentions kudraychik — a swindler. I can’t find that in the dictionary. It’s probably Slavic, not Yiddish. Max says, “There was a kudraychik, a Jewish barber, in the occupied zone after the war . . .”

You don’t hear that kind of language, except around Max.

A groysn dank, Max.

—

Check out my essay, “Some Acts of God Are Better Than Others,” in the Wall Street Journal (12/3/20). The link, here, takes you over the WSJ paywall.

December 9, 2020 2 Comments

GOOD BOY / BAD BOY

Whenever I came home for college vacation, my mother always suggested I go to the West Side with my father. (West Side meant the apartment biz.) My mother never went to the West Side. She didn’t go once! On the West Side I listened to my dad talk about boiler additives and sump pumps. My dad carried an Allen wrench to adjust boiler controls. I nearly died on the West Side. I was resentful. I had seen Roland Kirk at the Eastown Motor Hotel, East Cleveland; Sonny Stitt at Baker’s Keyboard Lounge, Detroit; Ben Webster at Ronnie Scott’s Club, London. And now I was on the West Side talking about radiator vents.

I watched the Dick Cavett Show and hung out with my high school buddies who were also home for college vacation. One guy was applying to medical school. Another was studying for the CPA exam. A friend was angling for a job as a reporter. The nightmare job: a high school acquaintance was studying nursing-home administration. How did he come up with that? He didn’t. His mother did. I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do, besides write novels. (Wrote them. Different story.)

I gave my parents tsuris. College was nonsense, I said, and I quit. I wound up in front of the draft board. The whole nine yards: bend over, touch your toes, spread your cheeks. I had a low number, 42, in the draft lottery. (You remember your lottery number if you’re of a certain age. It’s the closest our gang got to military service, except for G. Klein, who went to Annapolis.)

At the Selective Service office downtown, I took a mechanical aptitude exam. This test featured drawings of carburetors and brake shoes. The test stumped me. Many of the other test-takers loved it. A test about GTOs! These test-takers were mostly from my neighborhood. Draft boards went by neighborhoods, and my ‘hood had more than its share of greasers. At the end of the exams, I handed the draft-board doctor a list of my allergy medications and shots, and got out.

My parents didn’t go AWOL on me. They could have. My dad was bemused by my combat boots and jeans jacket, but he didn’t go Archie Bunker on me. My dad took his marching orders from Walter Lippmann, who called Vietnam a “quagmire.” My parents waited me out. My mother insisted I was still a good boy. She had been saying that since I was in kindergarten. I graduated college in due time, and I eventually went to the West Side — a lot. You’re a good boy. I can still hear my mother saying that.

—

I have a story in today’s Cleveland Plain Dealer about leaf blowers. Check it out here.

November 18, 2020 2 Comments

TRUMP, TRUMP, TRUMP

I used to write essays about what I had for breakfast, and get the articles in the Wall Street Journal and New York Times. This was pre-Trump. Now, to get in these papers, I need to write “Trump“ every paragraph to have a shot.

When I was in grade school, sixth graders attended a week-long camping retreat. My elementary school — Victory Park — shared our retreat with neighboring Sunview School. Our sixth-grade teacher, an ex-Marine, said we Victory Park boys should pay attention to Trump from Sunview. Our teacher said Trump’s dad owned Lyndhurst Lumber, and “she would be a good catch.”

Yes, Trump was a girl, and she had two p’s in her last name, Trumpp, but let’s ignore the second p here. Trump was pretty and friendly, and she played clarinet. In junior high, she and I sometimes shared the same music stand. I think she gave up clarinet to become a cheerleader, and she married a guy on the football team, and she was never heard from again — at least by me. No reunions, nothing. I recently Googled her and learned her husband took over Lyndhurst Lumber, so I suppose I could go in there and ask, “How’s Trump?” But let’s keep this virtual, not real.

A fellow classmate, Robby Stamps, hitchhiked to Trump’s house in Lyndhurst and dated her. Stamps was James Dean-esque. Hitchhiking at age 13! (Later Stamps was wounded at Kent State.) Stamps was fluid, culturally. His father was a gentile car salesman named Floyd, and his mom was Jewish. Stamps felt comfortable in both worlds. Remember, this was back when “ethnicity” could be a white thing.

Trump worked part-time at The Swedish Bakery at Mayfield and Green roads. I never went in there. I should have. But my shyness trumped all.

October 21, 2020 3 Comments

FANCY DANCING

My childhood friend Chap attended ballroom dance classes at the Alcazar Hotel. He had to wear white gloves. Chap’s dad worked for the Plain Dealer in home delivery, and his mom had been a professional banjo player. She was a realtor. Chap became “Chuck” in adulthood (he was always legally “Charles”) and got a job at the racetrack. He usually drove Corvettes. He liked to take the front plate off his Vettes to mess with the cops.

Chuck played quality trumpet in a soul band and was a flashy dresser. Lots of leather. He wanted to be Italian but wasn’t. He knew some racehorse owners at the track and eventually owned a horse or two. Also, he went to Bowling Green for a while, but college wasn’t his thing.

I haven’t seen Chap since 1992. I’d like to. He owes me $50 ($91 in today’s dollars). I advanced him the $50 for a meat tray for the wake of a mutual friend.

Nobody, except Chuck, in our neighborhood went to dance lessons, let alone the Alcazar — white gloves, tea and cookies. That program was called Mrs. Baltzer’s Dancing School. I found the name on the internet. Can you blame Chuck for rebelling and buying racehorses?

—

Here’s my op-ed from the Monday Wall Street Journal, “Landlords Have Bills Too.”

September 30, 2020 1 Comment

I REMEMBER, PART 2

I remember my mother’s apple sauce. Always lumpy.

I remember the 45 CTS bus to the Mayfield Road JCC.

I remember the shofar player missing every single note on Rosh Hashanah. He needed a trumpet mouthpiece.

I remember U.N. stamp souvenir sheets.

I remember the H-bomb.

I remember Pedwin loafers.

Bert Stratton and Ron Yarian (R), 2019 photo

I remember CBA (Chemical Bond Approach) Chemistry. I remember the teacher, Mr. Yarian. I saw him last year. He’s 84 and doing well.

I remember Charlene Cohen, the homecoming queen runner-up. I didn’t know her, by the way.

I remember the Cream-O-Freeze. You do, too. You don’t forget your childhood ice cream hangout. (My daughter’s favorite place was Draeger’s at Van Aken.)

I remember my mother writing: “Bert was absent from school yesterday due to religious observances.”

I remember How to Play Better Tennis by Bill Tilden.

—-

Afterthought:

These days there are Facebook groups specializing in South Euclid nostalgia. One site listed our dads’ occupations: plumber, insurance man, tailor, aerospace engineer, cop. One contributor to the list, Sal, said he was a barber and his dad and grandfather had been barbers, and his son was a barber. One guy wrote, “[We had] a family business on 89th and Hough until about a year or so after the riots. After that and an injury he sustained to the head from a robbery, he never was the same.” A woman wrote, “My father rented a building on 88th and Buckeye for his tools and supplies for his plumbing business.” I don’t remember.

July 29, 2020 7 Comments

THOSE ANTI-SEMITS!

My clarinet teacher, Harry Golub, was nicknamed the Bald Eagle. Harry was hairless. Howard Zuckerman, a student, gave Mr. Golub the nickname. Mr. Golub taught out of a South Euclid storefront. His dad ran a kosher butcher shop next door. Harry Golub owned the building. One of his better moves.

Zuckerman, like many junior high clarinetists, dropped out of private lessons around bar mitzvah time. I hung in through eleventh grade. During my high school years, Mr. Golub asked me how the clarinet dropouts were doing. I gave him some updates — so-and-so got straight A’s, so-and-so was on the tennis team.

Mr. Golub was often cranky because, for one thing, he didn’t get along with the music department at the high school. They wouldn’t buy instruments and sheet music from him, he claimed. Mr. Golub said the high school was in cahoots with another music store, the one out in goy land — Lyndhurst.

I occasionally ran into Mr. Golub years later at Yiddishe Cup gigs, and he was still railing against the school system. He said, “Those mumzers! Those anti-semits!” He had a point. It was a city (yidn) versus country (gentile) thing. Those gentiles in Lyndhurst were probably taken aback by the several thousand post-War Jews who moved into their farmland, built bungalows, studied hard (my friends did), and ate smelly salami. Mr. Golub, himself, ate Hebrew National sandwiches (from his dad’s kosher meat market) while giving lessons.

—

Here’s a story I wrote for today’s Cleveland Plain Dealer: “Peaceful enjoyment of the premises.”

July 1, 2020 6 Comments

COME THE REVOLUTION

I told my dad I couldn’t do pre-med because of the Revolution. How could I do eight years, minimum, of science and medicine during a revolution? My dad did not think I was nuts. (This was 1969.) He believed a revolution was coming, too. He read the papers and Newsweek, and followed Cronkite.

In Ann Arbor, the extremely radical Jesse James Gang splintered from the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). The Jesse James Gang leaders were Diana Oughton, Bill Ayers and Jim Mellon. These gedolim wore work boots (J.C. Penney), wire rims, and were Hollywood handsome. These leaders were several years older than undergrads like me. These radical kids’ “maturity” made them seem a lot more worldly. Seven years older is a big deal when you’re 19. Wire rims, plus long hair, and you got some looks, at least outside of Ann Arbor. You could get “hassled.”

The leader of the U. of Michigan student government was Marty McLaughlin, who wore Oxford-cloth shirts and was handsome too, but high school-y. (I should have been a fashion writer.) Meanwhile, the Jesse James Gang met in U. buildings and encouraged us to take it to the streets. Protestors threw rocks through store windows and carried NLF flags. An acquaintance, John Gettel, threw a rock through the Ann Arbor Bank. I was next to him. I was always “next to” somebody. I was Zelig, curious about revolution. I was at Kent State the night before. I didn’t want a revolution — and still don’t — and I knew it wasn’t going to be televised, so I tried to be there.

A couple years after college I saw Gettel on a street corner in Cleveland, passing out leaflets for Lyndon LaRouche. Gettel and his girlfriend were in Cleveland on assignment, mingling with the working class. I was on my way to my job managing apartments. I honked, said hi, and got out of there, and went to my job with the working class, who by the way hated the hippies.

Donald “Ducks” Wirtanen, a Finn from the U.P. and a college acquaintance of mine, got his jaw broken in a fight outside Hill Auditorium. I don’t remember why. I went to Cobo Hall to protest George Wallace. The funny thing, George Wallace was a good speaker, other than he was a racist.

In 1968 the Michigan Daily endorsed Hubert Humphrey and was criticized by Morris R., another acquaintance, for not endorsing Eldridge Cleaver of the Peace and Freedom Party.

The revolution was over by the end of 1970. Diana Oughton got blown up in her bomb factory in Greenwich Village. All politics were personal . . . “But the Man Can’t Bust our Music!” (Columbia Records). Marketing schemes and inner peace. Co-opt me, baby. Ecology was the next big thing. Back to the land. I didn’t do very well in Organic Chemistry. I blame it on the Revolution.

June 17, 2020 6 Comments

TAXI DRIVER

The taxicab supervisor, smoking a stogie, asked me, “Where’s Charity Hospital?”

“I don’t know,” I said.

“Where’s the Federal Building?”

“Ninth Street.”

“The Pick-Carter Hotel?”

“I don’t know.”

“The Hollenden House?”

“Downtown — St. Clair.”

“People want to know where their hotel is,” he said. He hired me. He worked for Universal Cab, a division of Yellow Cab. I drove welfare recipients with vouchers to hospitals, and workers to Republic Steel Works #4. I didn’t drive rich people; I thought I was going to drive rich people but it was mostly poor people. I picked up one rich guy, downtown. He said, “Severance Hall.”

I asked, “Are you Claudio Abbado?”

“How do you know!” he said. I told him I’d seen his photo in the Plain Dealer that morning. Afterward, I told a friend John I had driven “a conductor from Italy.”

“So why did he come here?” my friend said. John’s favorite expression was “Cleveland is the armpit of the nation.” (This was in 1970.)

My taxi-driving job went downhill after Abbado. A cabbie told me to carry a bat. He said, “A bat isn’t a concealed weapon. It’s legal.” One time I thought I was being followed by robbers. I got boxed in around St. Luke’s Hospital and escaped by going in reverse. Maybe I was imagining it. I was skittish. To understand, you have to have been around in 1970.

My cab stalled at Fairmount Circle. The engine smoked. I left the cab and hitchhiked back to the Noble Road garage. The supervisor said, “You mean you left your cab, son?”

“I knew I could get back here.”

“You mean you left your cab unattended?”

“Yes.”

Dead end.

February 26, 2020 4 Comments

YOU ARE A COMPLETE FAILURE

What happened to Sylvia Rimm? She used to be on public radio, dispensing childrearing advice. Rimm told my wife and me to subsume our individual personalities and create a united front to raise our kids. We didn’t. My wife, Alice, quoted Sylvia Rimm endlessly. Alice also quoted Eleanor Weisberger, Spock, Braselton and every other childrearing guru.

Alice wanted our kids to acquire a “sense of mastery” — of everything. Like going to Disney World was garbage, according to Alice, because our kids wouldn’t learn anything there. Actually, the kids learned a lot there. Teddy single-handedly planned the whole Disney World itinerary.

Our kids had so many lessons. I mean, ping pong lessons, tumbling lessons, Hebrew lessons, accordion lessons . . . Capoeira. What’s that?

My wife now gives lessons in everything.

Our youngest kid, Jack, learned to juggle by age 10. Our daughter, Lucy, became a Division 3 college athlete in diving. We didn’t allow much TV, except Mr. Rogers and once in a while The Simpsons. When our kids grew up, they immediately got TVs and watched every show made in the past 40 years.

I liked Bettelheim’s A Good Enough Parent. I liked the title. I swore at my kids. Was that so horrible? Probably hit my kids. Blocking it. One of my teenage kids took my car to an SAT test, and I needed the car for a gig because my music gear was in the trunk. I went to the SAT site and swore at the kid. An adult said to me, “Hey, ease up.” My outburst cost my child at least 30 points.

I snitched on some delinquent neighborhood kids who were very loud and rowdy. I called the police. The cop said, “Hey buddy, you’ve got a pretty short fuse.”

Are you perfect? Are you “slightly imperfect,” like my underwear? Are you good enough? Or are you a complete failure?

February 12, 2020 1 Comment

I REMEMBER

I remember Fail-Safe by Eugene Burdick and Harvey Wheeler. Who wrote the Fail part?

I remember Ted Williams could read the label on the ball.

When I was 10, I sent away to the Air Force Academy for a catalog and got one, along with an application.

I remember Larry and Norm Sherry of the Dodgers.

I remember Summit, the board game.

I remember Burger Chef.

I remember crepe dreidels hanging in the dining room.

I remember the Boy Scouts’ Life badge.

I remember my dad “hitting them out” to me in the park.

I remember playing “Exodus” on clarinet at the sixth-grade assembly. I also remember “Margie.”

I remember 1950-D nickels.

I remember “Hands Off Cuba” graffiti by the Rapid.

I remember slow-dancing to “Moon River” with a Christian Scientist.

I remember the Roxy.

I remember the JCC pop machine, and how it was frequently broken. The milk machine always worked. I drank a lot of chocolate milk. Maybe the useless pop machine was a parents’ conspiracy.

I remember Walter Lippmann in Newsweek.

I remember T.A. Davis tennis rackets.

I remember Rich Greenberg played Bobby McKinley — Chuck’s younger brother — in a national 16-and-under tennis tournament. Rich lost, but still, he played a McKinley.

I remember Harvey Greenberg got a 799 Math and 785 Verbal. (And this was before re-centering.)

I remember Chap’s GTO.

I remember Bruno Bornino’s “Big Beat” music column in the Cleveland Press. He also wrote “Pit Stop” about cars.

October 30, 2019 6 Comments